- 'A thought About' By Matt

- 4 Minute Read

I am very lucky to hold positions where I frequently get to talk to teachers and school leaders about their work and their day-to-day challenges. I also get to gain insight into how they balance and reconcile the range of factors that influence their short- to long-term planning as they work out how to navigate their day-to-day over weeks, terms and academic years. My conclusion: it’s really hard! (gasp – who knew?). School leaders and teachers have to find a way to make sense of a lot of complexity, little of which is of their making but all of which they deal with daily. This blog is about exploring the principles of curriculum and teaching approaches while schools and Trusts make decisions on how best to improve student outcomes.

I am very lucky to hold positions where I frequently get to talk to teachers and school leaders about their work and their day-to-day challenges. I also get to gain insight into how they balance and reconcile the range of factors that influence their short- to long-term planning as they work out how to navigate their day-to-day over weeks, terms and academic years. My conclusion: it’s really hard! (gasp – who knew?). School leaders and teachers have to find a way to make sense of a lot of complexity, little of which is of their making but all of which they deal with daily. This blog is about exploring the principles of curriculum and teaching approaches while schools and Trusts make decisions on how best to improve student outcomes.

I have found that there is a common perception underlying many concerns in schools and it can boil down to a single question:

How do I, as a school leader (feeling responsible for enacting effective change), make change happen (for the benefit of multiple stakeholders but primarily for students) while helping teachers (on whom we depend to run our classrooms) feel as if they’re in control of that change?

This question sums up an issue that I come across more commonly in discussions than almost any other when speaking with schools and educators. Isn’t that amazing? I find it incredible that there appears to be a such misunderstanding or lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities that the subject of change or ‘transformation’ repeatedly raises the spectre of conflict. In our respective vocations, we must all, be able to recognise what is within and without our immediate control while understanding and appreciating what lies well beyond. But I have found that those distinctions are very often blurred in the education sector.

Schools have long faced decisions about where to place control over aspects of their work. For instance, who has the agency to determine the geography curriculum; who needs to be consulted or informed about the new uniform policy; who decides what time the school day starts and ends; who chooses the course that will develop teachers into middle leaders? Within the classroom, teachers and their colleagues have ultimate responsibility for how children learn and can be supported to develop even better skills to do so. How this happens can be a bone of contention because we’re all individuals seeking to do our best. ‘What’ students learn is even more fraught with challenges.

Schools have long faced decisions about where to place control over aspects of their work. For instance, who has the agency to determine the geography curriculum; who needs to be consulted or informed about the new uniform policy; who decides what time the school day starts and ends; who chooses the course that will develop teachers into middle leaders? Within the classroom, teachers and their colleagues have ultimate responsibility for how children learn and can be supported to develop even better skills to do so. How this happens can be a bone of contention because we’re all individuals seeking to do our best. ‘What’ students learn is even more fraught with challenges.

The education system in England has gone through a range of changes and some would argue is never not changing. Some argue that this is a good thing and has improved the system of education. The wide range of opinions and discussions amongst educationalists on what schools should do, when and how, would suggest otherwise, particularly when the argument itself is in part responsible for the fragmented system we have here today. Where there is no consensus between schools and MATs, for example, on the distribution and position of curriculum control, there is a gaping hole in the sector’s collective agreement on what it (in this case the ‘curriculum’) is. That is despite the answer to that question being quite obvious to those I speak to outside of the sector itself (i.e. what children learn by being at school).

This apparent lack of sector-wide agreement on even the basics of a school’s purpose leaves open the door to debate, which teachers rightly feel they have a voice within but which I argue distracts them from the issues that they face and over which they have control. This creates an imbalance within the system between what students learn and how they learn. That in turn, relates to the space for a new market to develop in which commercial and charitable organisations now increasingly operate. I think this is a good thing, provided that the organisations involved are in it to solve the problems that schools are grappling with.

The challenge is that in order for these new organisations to be helpful to the sector they need to have a clear idea of what each school or MAT is doing or has done with their operations and where those aspects sit on the spectrum of centralized and standardized to local and autonomous. For the market’s vendors, establishing a clear idea of that and then how to proceed is anything but straightforward. Inconsistency in how schools and Trusts work is in itself no bad thing necessarily. Inconsistency can be a reflection of context, school types and students’ needs. But when schools and Trusts are seeking answers that the market can now help to answer, it is likely that the most efficient and effective market-generated solutions will be those that provide the fewest applicable and most scalable answers. The challenge I have found is that every discussion with a school leader involves superb detail and understanding of their school(s) and how learning is happening. But no two discussions result in the same conclusion because it seems that schools and Trusts are all on a journey of discovery about where ‘they are’ on the spectrum of autonomy to standardisation.

The challenge is that in order for these new organisations to be helpful to the sector they need to have a clear idea of what each school or MAT is doing or has done with their operations and where those aspects sit on the spectrum of centralized and standardized to local and autonomous. For the market’s vendors, establishing a clear idea of that and then how to proceed is anything but straightforward. Inconsistency in how schools and Trusts work is in itself no bad thing necessarily. Inconsistency can be a reflection of context, school types and students’ needs. But when schools and Trusts are seeking answers that the market can now help to answer, it is likely that the most efficient and effective market-generated solutions will be those that provide the fewest applicable and most scalable answers. The challenge I have found is that every discussion with a school leader involves superb detail and understanding of their school(s) and how learning is happening. But no two discussions result in the same conclusion because it seems that schools and Trusts are all on a journey of discovery about where ‘they are’ on the spectrum of autonomy to standardisation.

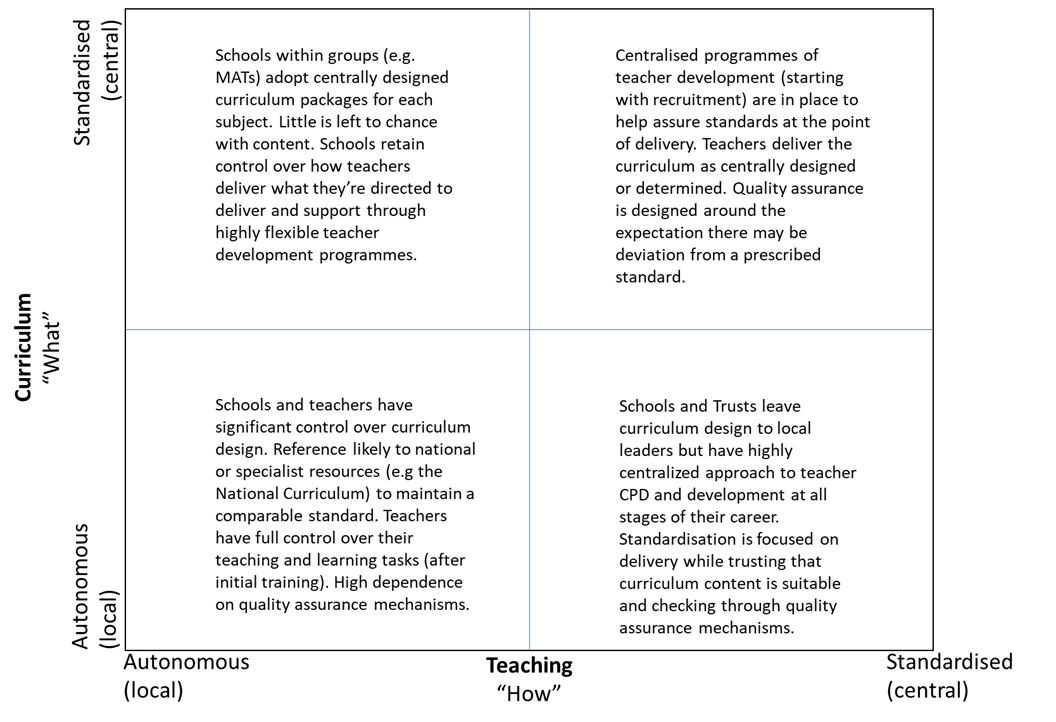

I have summarised my simple interpretation of the current landscape of curriculum and teaching centralisation vs autonomy below. I have focused on curriculum and teaching as two sides of the same coin that sit at the very heart of a school’s core purpose.

Schools are about helping students to learn the knowledge and skills that they need for their futures. Getting there (for each student) requires that both teaching and the curriculum are prepared, delivered and reviewed according to the decisions that have been taken. This means defining how they’re chosen and then utilising the best tools and resources possible to promote them. Schools and Trusts, were they to look at the quadrant above, could decide where they think they currently sit and whether that’s where they want to remain. If they intend to move, “why” becomes central to what happens next in order to effectively bridge the otherwise inevitable gap that this blog started off by positing as a question:

How do I, as a school leader (feeling responsible for enacting effective change), make change happen (for the benefit of multiple stakeholders but primarily for students’) while making teachers (on whom we depend to run our classrooms) feel as if they’re in control of that change.

If this situation resonates with you and your school, ONVU Learning can bridge the gaps and may provide that elusive win-win situation for school leaders, teachers and students alike.

Want to read from Matt? Click here

The School of the Future Guide is aimed at helping school leaders and teachers make informed choices when designing the learning environments of the future using existing and upcoming technologies, as they seek to prepare children for the rest of the 21st century – the result is a more efficient and competitive school.

KEEP IN TOUCH WITH ONVU LEARNING AND RECEIVE THE LATEST NEWS ON EDTECH, LESSON OBSERVATION, AND TEACHER TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT.